Unbreakable! Using Exercise to Preserve Bone Mineral Density After 40 Years

By Michael Ryan PhD, C. Ped (C)

Head of Product and Innovation, The Kintec Group

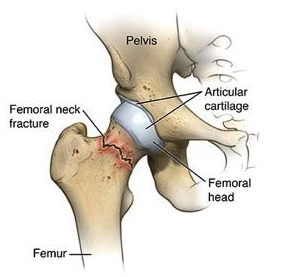

Hip Fractures are a big problem. The human hip is one of the most protected joints in our body. Involving our body’s two largest bones in the femur and the pelvic innominate, then surrounded by multiple layers of muscle and soft tissue, it requires an immense amount of force (think falling off a 10′ ladder onto concrete) to fracture these bones under normal, health circumstances. Despite this, the health care system still sees ~30,000 cases of fractured hips each year in Canada!1

Paradoxically, the most common reason for these fractures is simply losing balance and falling on your side while walking (we’ll address why in the next section).

After fracturing your hip, it is not difficult to imagine how difficult it would be to move about, notwithstanding the seriousness of the injury itself. Not only can you not bear weight on the affected leg, but the stress on the pelvis from standing on the unaffected side would also be unbearable, rendering the patient bed-or wheelchair-bound for weeks to months while the fracture heals.

After virtually zero weight-bearing activity for a prolonged time, the largest muscles in the body that support the hip begin to weaken and atrophy; muscles that play important roles in helping maintain our overall health and manage metabolic equilibrium. We can now appreciate the sobering statistic that 25 % of patients that fracture their hip will die of any cause within the next 12-months!2

In order to understand why hip fractures occur, we have to first address an even larger underlying problem. Osteoporosis.

Osteoporosis is a Leading Cause for Fractures

Hip fractures are considered a ‘fracture of frailty’ given the overwhelming numbers of patients who are older than 50 and also present with low bone mineral density, a condition referred to as osteoporosis. Osteoporosis is simply when we lose mineral content in our bones resulting in reduced strength and fracture resistance. A diagnosis of osteoporosis is done by having your doctor schedule a Bone Mineral Density test using a device called dual X-ray absorptiometry or DEXA. There are no other major symptoms of osteoporosis; therefore, most people who have it, don’t know it. Osteoporosis Canada is a great resource for more information on testing osteoporosis including listing who should be getting tested. A simple rule of thumb: if you’re over 65, get tested!

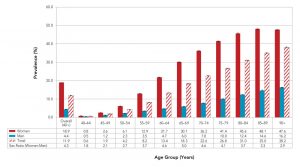

Figure 2: Prevalence of diagnosed osteoporosis among Canadians 40 years and older, by age group and sex from 2015-2016.

One thing is known for certain – not enough people are getting tested! Of those who had an osteoporosis-related fracture, less than 20% received an osteoporosis diagnosis, underwent a bone mineral density (BMD) test or received a prescription for an osteoporosis-related medication within one year of the fracture. 2 Twenty percent is a staggeringly low number! Essentially most people who had a fracture of frailty never knew they were at such a high risk! Without question, many of these fractures could have been avoided if people simply knew their vulnerability and took steps to both prevent falls while restoring bone mass. The next section outlines the importance of exercise and some ways to remove barriers to activity.

Using Activity to Strengthen Bones

While most people think of exercise for osteoporosis, they don’t imagine 70-year-olds with low bone mineral density performing deadlifts! But that’s exactly what Dr. Belinda Beck at Griffith University intended when she designed The LIFTMOR Study. In 100 post-menopausal women with osteopenia, she examined the impact of twice-weekly, 30-minute supervised high-intensity resistance training versus more traditional home-based low-intensity exercise.3 In the end, not only was the high-intensity group superior to the control exercise program, but there were also no adverse events or fractures observed, suggesting supervised high-intensity resistance exercise is safe for postmenopausal women with low to very-low bone mass.

Outcomes from Dr. Beck’s research helped lead a consensus statement on the role of exercise in the prevention and treatment of low bone mass.4 Importantly, the greatest skeletal benefits were seen when resistance exercise programs were:

- Progressively increased over time (i.e., there are incremental increases in weight each week);

- Magnitude of loading was high (around 80-85% of 1 repetition maximum);

- Training was performed at least twice per week;

- Large muscles crossing the hip and spine were targeted – think beyond simple arm curls!

Walking alone is not enough, lifting 5lbs dumbbells is not enough, gardening is not enough. Our bones require a substantial amount of external loading to stimulate positive remodeling. Not sure where to start? Consult your local physiotherapist on how you can begin to incorporate elements of the LIFTMOR trial into your weekly routine (we’ve included a copy of the research article [here] for reference).

Removing Barriers to Movement with Insoles & Footwear

While walking alone does not result in significant gains in bone mass in postmenopausal women (surprising hey!), regular aerobic activity does play a vital role in maintaining both the muscle tissue and coordination that are needed to preserve balance. Remember, it’s best to tackle the hip fracture problem from both sides: maintain your balance and stability to avoid falling, while also maintaining bone mass so that you won’t suffer a fracture of frailty if you do.

One important intervention to help augment balance are in-shoe inserts or orthotics. Insoles can work through a variety of different mechanisms to assist postural stability. The most common approach is simply using a contoured arch that essentially brings the ground up to the foot providing more neurosensory awareness of our body’s position.5 Other techniques use altered textures to amplify this neurosensory awareness by attempting to preferentially activate certain receptors in the skin or make these receptors resistant to becoming desensitized.6

Footwear can also play an important role in maintaining balance. Nowadays athletic footwear can vary substantially in the thickness and softness of the sole, or even the pitch of the heel (how elevated the heel is over the forefoot). If the goal is to maximize stability, then wearing footwear that is less soft, has a reduced heel pitch (ideally less than 6mm), and incorporates lateral flaring or other stabilizing features is ideal. Shoes such as the Columbia Montrail F.K.T is a great option for stability and traction for many outdoor activities.

Have questions about the role of insoles or footwear for your bone-health regimen?

Book a One2One appointment with a Canadian Certified Pedorthist to have an assessment of your unique biomechanics and medical history.

Our One2One program will provide you with the highest level of safety and personalized service to keep you active and on your feet for life.

No Comments